AP Syllabus focus:

‘A solid may be described by a base region in the plane and a known cross-sectional shape, such as a square or rectangle, perpendicular to a coordinate axis.’

Solids with known cross sections are three-dimensional objects whose volumes are determined by integrating the area of square or rectangular slices built on a planar base region.

Understanding Solids with Known Cross Sections

When studying solids with known square or rectangular cross sections, students analyze a region in the plane—called the base region—and determine how three-dimensional volume forms when identical-shape slices rise perpendicularly from this base. These solids are fundamental in applications of integration because they demonstrate how accumulated area creates volume.

The base region is typically bounded by curves or lines in the coordinate plane. From this region, slices perpendicular to either the x-axis or y-axis are imagined. Each slice has a known two-dimensional shape—most commonly a square or rectangle—whose dimensions depend on the geometry of the base.

Base Region: The two-dimensional area in the coordinate plane over which cross-sectional slices are constructed to form a three-dimensional solid.

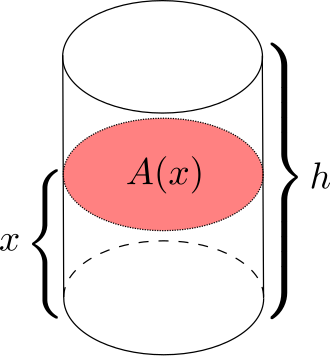

At each point along the chosen axis, the solid is sliced by a plane perpendicular to that axis, and the area of this slice is denoted by A(x)A(x)A(x) or A(y)A(y)A(y).

A solid is represented as a cylinder of height hhh, sliced by a plane at height xxx. The shaded region shows the cross-sectional area A(x)A(x)A(x) used in the volume integral. Although this particular cross section is circular rather than square or rectangular, the picture illustrates the same idea of building volume from stacked cross-sectional areas. Source.

Once the base is identified, the volume is found by integrating the cross-sectional area across the relevant interval. This process connects geometric reasoning with integration as accumulation.

Cross Sections Perpendicular to a Coordinate Axis

A cross section is formed by slicing the solid with a plane perpendicular to a chosen axis. The direction of these slices determines how a student expresses dimensions of the shape in terms of a variable.

Slices perpendicular to the x-axis use as the variable of integration and take their dimensions from functions describing vertical distance.

Slices perpendicular to the y-axis use as the variable of integration and rely on horizontal distances.

Cross Section: A planar slice of a solid whose shape and dimensions determine the integrand used to compute volume.

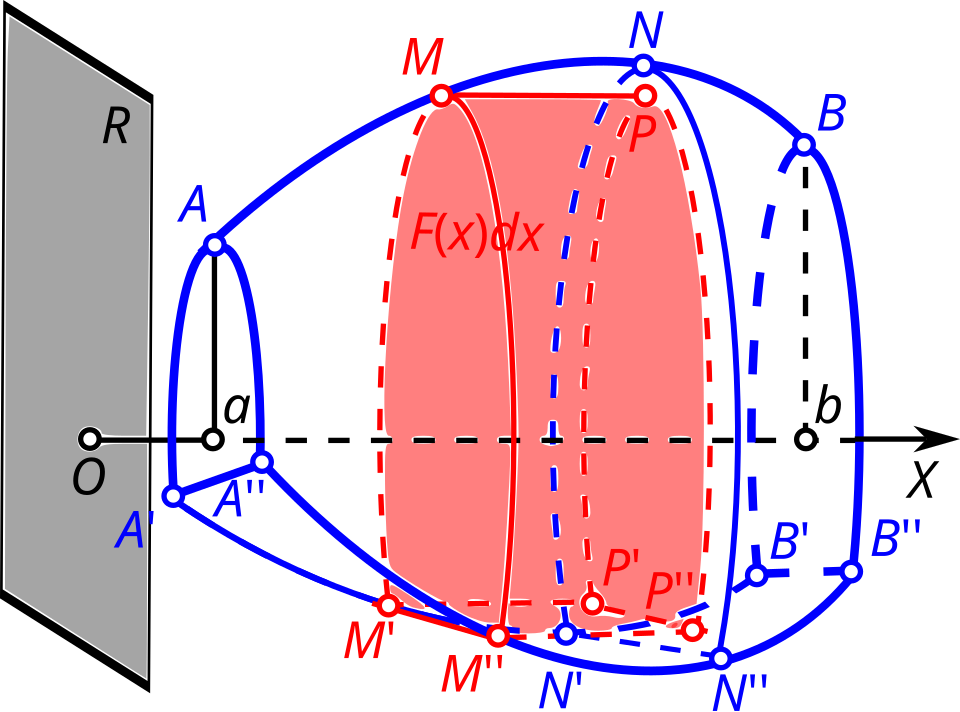

A solid with known square or rectangular cross sections can be viewed as an accumulation of many thin slices, each slice having area A(x)A(x)A(x) (or A(y)A(y)A(y)) and small thickness Δx\Delta xΔx (or Δy\Delta yΔy).

A general solid is shown with many parallel cross sections drawn inside it. Each slice represents a thin layer of volume whose area contributes to the total when summed by an integral. The diagram is generic and does not assume square or rectangular cross sections, but the same picture applies when every slice has a specified square or rectangular shape. Source.

By choosing an appropriate axis of perpendicular slicing, students often simplify expressions for side lengths or widths of the shapes used.

Square Cross Sections

When the slices are squares, the side length of each square depends on the length of the segment in the base region perpendicular to the slicing direction. A square’s area is determined entirely by this single dimension, so understanding how the side length varies across the interval is essential.

If the square’s side length is expressed as a function of or , then the area of each slice becomes the square of that expression. This area then becomes the integrand for the volume.

= Area of a square cross section as a function of (square units)

Because square cross sections rely on a single dimension, they provide a straightforward setting for connecting geometric formulas with definite integrals.

Rectangular Cross Sections

For solids with rectangular cross sections, the slices have two varying dimensions: a base (taken from the planar region) and a height (often specified explicitly in the problem). Unlike squares, rectangles require students to consider how both dimensions behave across the interval.

Typical structures involving rectangular cross sections include:

A fixed height and variable base length.

A base determined by the distance between two curves.

A height defined as a multiple or fraction of the base.

Rectangular Cross Section: A slice whose area equals the product of a variable base length and a specified or variable height.

When the rectangular dimensions are known, the area of each slice becomes the integrand for computing the volume through integration.

Building the Volume Integral

Setting up a cross-sectional volume problem involves interpreting geometric information in the plane and translating it into a continuous accumulation process.

Steps for Constructing the Integral

Identify the axis of perpendicular slicing: Determine whether slices are perpendicular to the x- or y-axis.

Find the limits of integration: Use the endpoints of the interval describing the base region in the chosen variable.

Determine the dimension(s) of the slice:

For squares, identify the length of the side.

For rectangles, identify both the base and height.

Form the area function or :

Square area: side length squared.

Rectangle area: base multiplied by height.

Write the definite integral of the area function over the interval.

Evaluate the integral to obtain the volume.

= Cross-sectional area expressed in terms of the variable (square units)

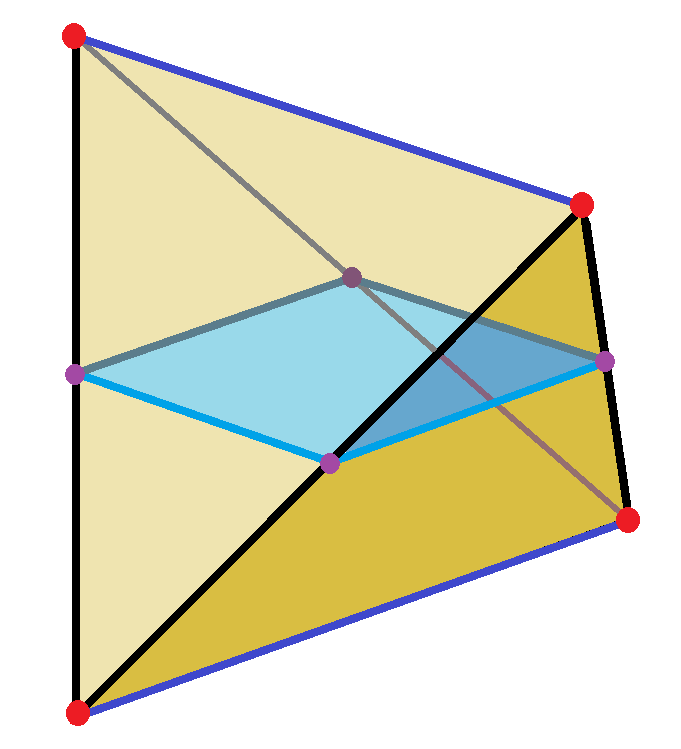

Knowing that each cross section is a square means the area function is A(x)=[s(x)]2A(x) = [s(x)]^{2}A(x)=[s(x)]2, where s(x)s(x)s(x) is the side length determined by the base region.

A regular tetrahedron is sliced by a plane so that the intersection forms a perfect square. This demonstrates how a solid can possess planar cross sections of a fixed shape, such as a square. The context goes beyond the AP syllabus, but the picture is useful for visualizing the idea of specifying a square cross section inside a three-dimensional solid. Source.

Through this method, the volume emerges as the accumulated area of infinitely many thin slices, each shaped according to the specified cross section. This interpretation emphasizes the calculus idea of summing continuous change across an interval.

FAQ

Choose the axis that makes the varying dimension of the slice easiest to express.

If the side length or the base of the rectangle is naturally described as a horizontal distance, slice perpendicular to the y-axis.

If it is more naturally a vertical distance, slice perpendicular to the x-axis.

This choice often avoids splitting the region into multiple integrals.

Yes. Although many problems use a constant height multiplier, the height can vary with x or y.

In such cases, the area of the rectangle becomes base times height, and both expressions must be written in terms of the same variable.

This may produce more complex integrands, but the volume calculation remains the integral of area over the chosen interval.

You may still set up the cross-sectional volume as long as you can express the relevant dimension.

For irregular boundaries:

• Use piecewise descriptions if different parts of the region require separate expressions.

• Sketching the region often clarifies which distances correspond to side lengths or bases.

• Splitting the integral into subintervals may be required if one expression cannot represent the entire width or height.

No. The integrand reflects the formula for the area of the slice.

If the side length or height involves non-polynomial expressions (such as roots or trigonometric functions), the resulting area may be non-polynomial.

This does not change the method: the volume still equals the integral of the cross-sectional area.

These solids are not formed by revolving regions, so no circular geometry is involved.

Instead, the slices are defined directly by the shape of the cross section.

Because the slices have fixed shapes (squares or rectangles), the contribution to the volume is determined only by the linear dimensions from the base region, making integration based solely on area rather than rotation.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A solid has a base on the interval 0 ≤ x ≤ 4. At each value of x, the cross section perpendicular to the x-axis is a square. The side length of each square is given by s(x) = 3x.

(a) Write an expression for the area of a cross section at x.

(b) Write, but do not evaluate, a definite integral that represents the volume of the solid.

Question 1

(a)

• Correct area expression A(x) = (3x)² = 9x². (1 mark)

(b)

• Correct integral for volume V = ∫ from 0 to 4 of 9x² dx. (1 mark)

(Up to 2 marks total)

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A solid has a base in the xy-plane bounded by the curves y = 0, y = 2, and x = y + 1. Cross sections taken perpendicular to the y-axis are rectangles whose heights are twice the length of the base region at that value of y.

(a) Determine an expression for the width of the rectangular cross section at a fixed value of y.

(b) Hence write an expression for the area of a cross section at y.

(c) Write a definite integral that represents the volume of the solid.

(d) Evaluate the integral to find the volume.

Question 2

(a)

• Correct width: horizontal distance from x = y + 1 to x = 0, giving width = y + 1. (1 mark)

(b)

• Correct rectangular height: 2(y + 1).

• Correct area expression A(y) = (y + 1) multiplied by 2(y + 1) = 2(y + 1)². (1–2 marks)

(c)

• Correct integral for volume: V = ∫ from y = 0 to 2 of 2(y + 1)² dy. (1 mark)

(d)

• Correct evaluation of integral:

Integrand expanded: 2(y + 1)² = 2(y² + 2y + 1).

Integral: 2[(y³)/3 + y² + y] from 0 to 2.

Value: 2[(8/3) + 4 + 2] = 2(8/3 + 6) = 2(26/3) = 52/3.

• Final answer: 52/3. (1–2 marks)

(Up to 6 marks total)